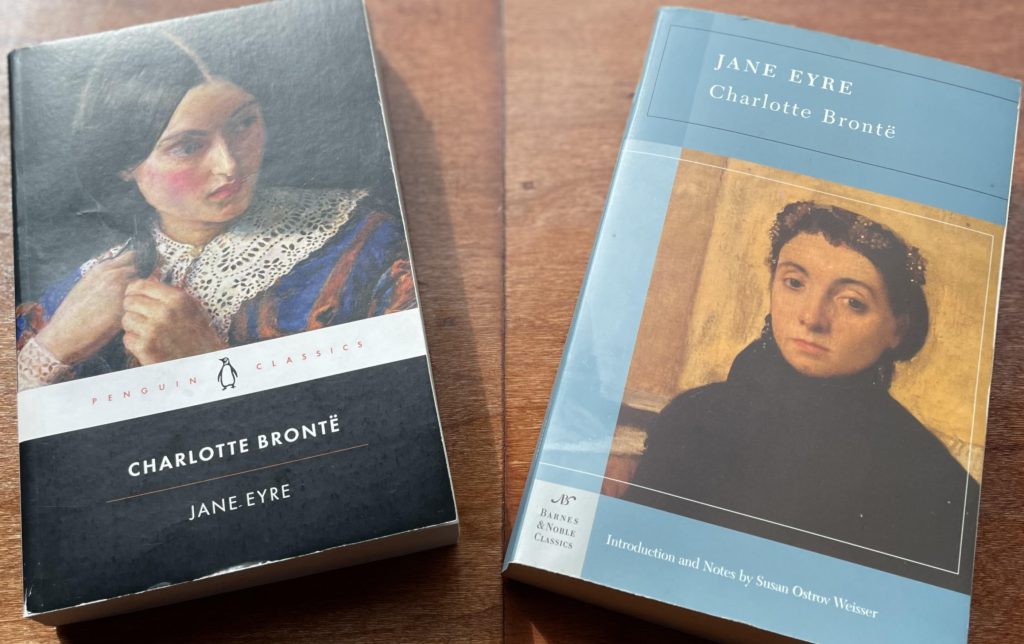

Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë, 1847

(Spoilers)

You know that get-to-know-you question, “if you could have dinner with any famous person, dead or alive, who would you choose?”

My answer is UNDOUBTEDLY Charlotte Brontë because if she is anything like Jane Eyre, her beloved titular protagonist, I would love to pick up some of the boss queen slay business she was in the custom of being, especially back in 1847 (let me say that again in all caps, EIGHTEEN FORTY SEVEN) when women were typically expected not to have such a secure sense of self and ability.

The story of Jane Eyre begins in childhood. 10 years old, Jane lives in Gateshead Hall, the estate of her deceased Uncle’s begrudged wife (Aunt Reed) with her 3 spoiled cousins, and their kind servant, Bessie. Prone to fits of anger and outbursts (a consequence of the intense maltreatment by her miserable Aunt Reed and cousins), she is one day punished by being sent into the room where her Uncle’s death occurred and, frightened, faints. Her doctor suggests Jane be sent to a boarding school for girls (Lowood), an idea Aunt Reed jumps at and sends her off, but not before making some unkindly remarks about her to the headmaster, Mr. Brockelhurst, who then takes Aunt Reed’s place as her new maltreater (haters gon’ hate, Jane, but you do you girlie).

Brontë, genius she is, doesn’t overlook the fact that a young girl who’s been shown no love all her life would likely show no love back; so at Lowood we meet Helen Burns, young Jane’s foil, who preaches forgiveness and peace, teaching Jane to let go of the animosity which has been so fostered in her up until this point. In what becomes the first scene of the novel that had me crying, Helen passes from tuberculosis, Jane by her side, and Jane narrates that the word “resurgam” is written on her gravestone, meaning I shall rise again, which she does through Jane’s spirit in adulthood.

Jane moves on from Lowood at 18 to become a governess for a young Adele at Thornfield Hall, the estate of the wealthy and surly, man of high social-status, Mr. Rochester—this setting remains for the bulk of the novel. Though she and Rochester do fall in love, Jane’s initial response to meeting her “master” (gag) is to be wary of his ‘its-giving-colonizer’ ego (men!) and his wayward desire to control her. Though their relationship is characterized largely by her docility and his domination, she continues to stay true to her pride and not be changed, despite his urging that she conform to a female of higher society, especially during the time of their eventual engagement and while planning their evidently rushed wedding.

It is revealed, while up at the ALTAR (real good timing, here), that Rochester’s insistence on rushing their wedding was not in fact from a carnal need to love and marry Jane, as one sweet romantic like I may have thought, but from a fear that the news of this wedding would reach the brother of his OTHER wife (yes you read that right) who has, for the entirety of the novel, been locked up in the Thornfield attic like a deranged lunatic. Welcome, the novel’s other boss queen slay, Bertha Mason! (this is a joke, she is not painted positively at all; in fact, she is barely a character, only described as being a maniacal, monstrous woman of mixed race from the West Indies, which, please note, plays into the sick, colonial, patriarchal domination fantasy of white mem to capture and control the dark, hypersexual foreign woman with a ravenous appetite).

Are you disturbed? Jane was. Jane tells Rochester off, Rochester throws a tantrum akin to that of a 4-year-old who gets chastised for coloring the walls, and Jane leaves him in the middle of the night despite his characteristic attempts at gaslighting her into staying. She wanders through the grasslands and a village beautifully painted in snow (though I’m sure she was less than appreciative of the scenery, as she is destitute, hungry, and freezing), and while nearing close to death, she finds a humble home (Moor House) with an austere but virtuous man and two kind-hearted women (who happen to be her long-lost cousins with whom she shares a mutual Uncle who has left her 20,000 pounds, mostly because storyworlds are better than our worlds).

Here, among these people, Jane finds comfort, companionship, and family, and, as she has found these things for herself without Rochester (also after a little drama between her and St. John), she decides to return to Thornfield, where she finds a burnt down manor of ruins after Bertha, our “madwoman in the attic,” set the estate in flames (I can’t say I blame her, Rochester was bound to get his comeuppance somehow).

The novel comes to fruition when Jane finds Rochester maimed from the fire, and she marries him at last. *Cries in fulfillment.*

Oh, goodness, what a masterpiece.

This novel is a whirlwind of romantic and gothic elements, and it’s one of the most beautifully written stories many of us have ever read. This was, for me, the novel which got me into reading all those many moons ago, and, as I now know through the booktok community, Jane Eyre being that book is an experience that many of us young girlies have had.

It’s notable that, though her romance with Rochester may be the most exciting aspect of the novel for some of us hopeless romantics, Jane makes clear that her romantic relationship with Rochester comes second to her own sense of self-respect, pride, and autonomy. This is a novel in which a young girl breaks a cycle of patriarchy (her own, while Bertha’s should be acknowledged as having been unredeemed and fatal), and forgoes romantic love where she is not an equal to her partner in order to find the more substantial qualities of companionship and freedom; in fact, she only returns to Rochester once he has physically become weak through his maiming from the fire. This symbolizes his inability to yield such power over her any longer. This aspect of the novel lends to classifying Jane Eyre by some as an “anti-romance,” since the homosocial element of Jane’s search for companionship, beginning in her childhood, is heavier throughout than her desire to find romance.

Other parts of Jane Eyre which ROCK are the supernatural elements, which are slight but do create a foreboding atmosphere which foreshadows the disturbing twist of Bertha at the novel’s climax; this is in a few places—the “red room” where young Jane is sent as punishment and faints from fear in the beginning of the novel, the frightening sounds of laughter which Jane hears through Thornfield on multiple occasions (which are in fact Bertha, but readers do not know this), the first fire which is mysteriously started (which Jane saves Rochester from and is quickly cleared), the dark woman Jane sees ripping up her wedding veil (which readers now know is Bertha), and the supernatural calling Jane hears from Rochester while at Moor House which incites her to return home.

This book could be no less than a 5/5, but could DEFINITELY be more. I don’t know that I will ever find a love deeper than the one I have for this novel. Picking it up for the first time in a while, I am incredibly tempted to lose myself in it once more, especially to search for quotes, which are dismal here, as I hadn’t yet begun my habit of collecting quotes during my first (and second) read of this novel—though this may have been for the best, as I can imagine if I had been in the habit of collecting quotes, I would have highlighted more sentences than not.

Here is what I do have: (this first one is my all time favorite novel quote)

Most true is it that “beauty is in the eye of the gazer.” My master’s colorless, olive face, square, massive brow, broad and jetty eyebrows, deep eyes, strong features, firm, grim mouth—all energy, decision, will—were not beautiful, according to rule, but they were more than beautiful to me; they were fill of an interest, an influence that quite mastered me—that took my feelings from my own power and fettered them in his. I had not intended to love him; the reader knows I had wrought hard to extirpate from my soul the germs of love there detected; and now, at the first renewed view of him, they spontaneously revived, green and strong! He made me love him without looking at me.

While arranging my hair, I looked at my face in the glass, and felt it was no longer plain: there was hope in its aspect and life in its colour; amd my eyes seemed as if they had beheld the fount of fruition, and borrowed beams from the lustrous ripple. I had often been unwilling to look at my master, because I feared he could not be pleased by my look; but I was sure I might lift my face to his now, and not cool his affection by its expression. I took a plain but clean and light summer dress from my drawer and put it on: it seemed no attire had ever so well become me, because none had I ever women in so blissful a mood.